- Home

- Gerry Bowler

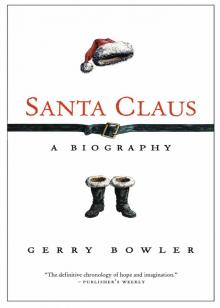

Santa Claus

Santa Claus Read online

ALSO BY GERRY BOWLER

The World Encyclopedia of Christmas (2000)

Copyright © 2005 by Gerry Bowler

Hardcover edition published 2005

Trade paperback edition published 2007

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher – or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency – is an infringement of the copyright law.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Bowler, Gerald, 1948–

Santa Claus : a biography / Gerry Bowler.

eISBN: 978-1-55199-608-0

1. Santa Claus. 2. Nicholas, Saint, Bishop of Myra. I. Title.

GT4992.B68 2005 394.2663 C2005-902310-4

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program and that of the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Media Development Corporation’s Ontario Book Initiative. We further acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program.

McClelland & Stewart Ltd.

75 Sherbourne Street

Toronto, Ontario

M5A 2P9

www.mcclelland.com

v3.1

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

I His Long Gestation and Obscure Birth

II His Youth and Character Development

Photo Insert 1

III Santa as Advocate

IV Santa the Adman

V Santa the Warrior

Photo Insert 2

VI Santa at the Movies (and in the Jukebox Too)

VII Does Santa Have a Future?

Acknowledgements

Notes

Picture Credits

Introduction

Christmas is the most important season of our existence. We spend at least one month out of each year of our lives under the spell of the planet’s most widely celebrated holiday. At no other time are our feelings as intense; at no other time are we so caught up in a relentless round of preparation, enjoyment, and recovery. We plan, we drive, we shop, we buy – thus making merry the hearts of jewellers, booksellers, and purveyors of toys, perfumes, and motorized tie racks. We wrap, we conceal, we wait. We clean and decorate; we bake, cook, brew, and ice; we fast, worship, pray, and celebrate. We visit, we host; we tell stories to our children (sometimes true ones) and listen to the wishes (always sincere) they tell us. We write cards, address envelopes, and lick stamps. We renew our acquaintance with holly, pine boughs, gingerbread, marzipan, and tinsel. We seek out, transport, and erect in our homes dead trees, which we then ornament with baubles that hold meaning only for that month. We sing songs, some of great spiritual power, some of consummate silliness – at what other time of the year is our speech of reindeer, angels, elves, chestnuts, and kings? We joyfully open gifts in the presence of loved ones and think sadly of those who are absent. We eat, drink, and are bloated. Too much is our catch phrase – we are too generous, too gluttonous, too sentimental, and too tired. We vow that next year will be different, forgetting that excess lies at the heart of celebration.

If, for reasons of religion or irreligion, we choose not to participate directly in the Christmas phenomenon, we discover that its reach is everywhere. There is no way to avoid the holiday music on the radio or in the malls; we are assailed by hearty greetings, beset by long lineups, and daunted by the hunt for a vacant parking spot. If we are repelled by the consumerism of our neighbours or made melancholy by their happiness, we dare not voice our unease, lest we be called “Grinch,” or worse. Christmas is inescapable.

Two deities preside over the season. One is the baby Jesus, the divine infant, God incarnate to all Christians, adored by shepherds and angelic hosts, celebrated in carols, stained glass, and midnight masses. Numberless are the books, films, and works of art dedicated to exploring his significance. Christmas marks his birth two thousand years ago in a Middle Eastern stable.

The other is Santa Claus, the dominant fictional character in our world. Neither Mickey Mouse nor Sherlock Holmes, Ronald McDonald nor Harry Potter wields a fraction of the influence that Santa does. He is a fundamental part of the industrialized economy; he is a spur to consumption but also to charitable giving. He provides employment for millions, encourages good behaviour in the young, and unifies families and nations in seasonal rituals. He is celebrated in story, song, movies, lawn displays, and malls. His image is recognized and loved all around the planet.

All of Santa’s prestige derives from his role as the chief gift-bringer during the celebration of Christmas. Though Christmas is an ancient festival and one with which gifts have been associated from the very beginning, Santa Claus himself is a rather more recent arrival. Where did he come from? Is he a figure of mythology, a creation of literature, a tool of clever capitalists? How did he come to hold sway over such a large part of our existence? An account of his life will tell us much about the power of memory and magic, the duties of childhood and parenting, the clash of the commercial and the sacred.

I

His Long Gestation and Obscure Birth

A Russian icon from the twelfth century shows Saint Nicholas as a stern Orthodox bishop, easy to visualize as an authority figure who would be “cruel in correctyng.” (photo credit 1.1)

One evening in Bethlehem, in the twenty-sixth year of the reign of Caesar Augustus, a party of astrologer-magicians knocked on the door of a house where a young family from Nazareth was staying. Ushered into the presence of the new mother and her child, these foreign visitors, whom legend would number as three and name Gaspar, Melchior, and Balthasar, unwrapped their bundles and presented the baby with gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Thus were the very first Christmas presents delivered.

Strangely, centuries would pass before the connection between the celebration of the nativity of Jesus and gifts became widespread. Early Christians thought that marking the birthday of their Lord was not unlike the way pagans honoured their rulers. The Alexandrian theologian Origen in the third century spoke out against observing the anniversary of Christ’s birth as if he were some sort of “King Pharaoh.” Believers tried to live inconspicuously among their neighbours in the Roman Empire and walked a fine line between harmless cultural accommodation and taking part in forbidden heathen ceremonies. Since most festivals of the time had strong religious components, it is not surprising that Christian leaders had serious misgivings about how their flock celebrated the holidays, particularly those extravagant festivities that marked the end of the year.

The Roman world began their festivals in late December with Saturnalia, which during the five days starting on December 17 honoured Saturn, an ancient agricultural deity. All work, except the preparation of food, was forbidden, and the world, for a short time, was turned upside down. Slaves and masters temporarily reversed roles, and a Lord of Misrule was elected to oversee this brief return to an older Golden Age. It was a time of obligatory merriment, banqueting, gambling, suspension of quarrels, cross-dressing, and masquerades. Houses were decorated with candles and greenery, and small presents were exchanged between friends; children were given little dolls (perhaps as a token of the time when human sacrifices were made to ensure fertility of the crop). Next came the winter solstice, Brumalia, and after its introduction in A.D. 286, the Feast of the Unconquered Sun – a day meant to inspire patriotism and good thoughts about the emper

or, and this led to the Kalends of January, which marked the beginning of the New Year.

The fourth-century pagan Libanius of Antioch had this to say about the holiday:

The festival of the Kalends is celebrated everywhere as far as the limits of the Roman Empire extend.… The impulse to spend seizes everyone.… People are not only generous towards themselves, but also towards their fellow-men. A stream of presents pours itself out on all sides.… The Kalends festival banishes all that is connected with toil, and allows men to give themselves up to undisturbed enjoyment.… Another great quality of the festival is that it teaches men not to hold too fast to their money, but to part with it and let it pass into other hands.

Political changes in the fourth century cleared the way for Christianity, first as one religion tolerated among many and then the empire’s official faith. This led to the open celebration of Christmas and the choice of December 25 as its date. Saint Maximus of Turin stood Origen’s anti-celebratory argument on its head, saying:

You well know what joy and what a gathering there is when the birthday of the emperor of this world is to be celebrated; how his generals and princes and soldiers, arrayed in silk garments and girt with precious belts worked with shining gold, seek to enter the king’s presence in more brilliant fashion than usual.… If, therefore, brethren, those of this world celebrate the birthday of an earthly king with such an outlay for the sake of the glory of the present honor, with what solicitude ought we to celebrate the birthday of our eternal king Jesus Christ. Who in return for our devotion will bestow on us not temporal but eternal glory!

Christianity also brought an end to many of the old pagan holidays, but inhabitants of the Roman world were still able to enjoy the trappings of these midwinter festivals; observances that had accompanied Saturnalia and the Kalends were now transferred to the newer Christian holidays, Christmas and Epiphany. Despite frequent exhortations to the contrary, citizens continued to mark the new days with old ways. In January A.D. 400, Bishop Asterius of Amasea delivered a sermon in which he criticized Christians for the manner in which they gave holiday gifts.

Oh, the absurdity of it! All stalk about open-mouthed, hoping to receive something from one another. Those who have given are dejected; those who have received a gift do not retain it, for the present is handed on from one to another, and he who received it from an inferior gives it to a superior. The money of this festival is as unstable as the ball of boys at play, for it is passed quickly on from me to my neighbor. It is but a new form of bribery and servility, having inevitably linked with it the element of necessity. For the more eminent and respectable man shames one into giving. A person of lower rank asks outright, and it all moves by degrees toward the pockets of the most eminent men.…

This festival teaches even the little children, artless and simple, to be greedy, and accustoms them to go from house to house and to offer novel gifts, fruits covered with silver tinsel. For these they receive in return gifts double their value, and thus the tender minds of the young begin to be impressed with that which is commercial and sordid.

This was a frequent lament of churchmen over the next few centuries, and though religious authorities suppressed some of the more egregious behaviour – such as cross-dressing or parading about in animal skins – the traditional giving of gifts at midwinter and New Year would persist.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the Christmas season (and we must remember that Christmas has always been a season and not a single day) was associated with presents. Gifts were given in a number of ways and for different reasons. Feudal relationships, key to the smooth functioning of medieval society, were solidified by them. Gifts went up and down the social ladder and were precisely calculated. Courtiers would give gifts to the king to demonstrate their fidelity, kings and popes to show their munificence and the advantages of loyal service. An Italian visitor to England in the late 1400s noted: “The subjectes send to their superiors, and the noble personages geve to the kynges some great gifts, and to gratifie their kyndnesse, doth liberally reward them with some thing again.” (Queen Elizabeth 1 icily recorded the value of each gift she was given, many of which were cash.) At this end of the social scale, gifts might include a knighthood, a choice estate, or entry into a chivalric order. A look at the financial accounts of authority figures ranging from a humble country squire to a mighty monarch would reveal a long list of expenditures on seasonal gifts for servants, musicians, choirboys, friends, and neighbours. Tenants might be required to give thoughtful tokens to their landlords, and landlords might be required to feast their tenants over the Christmas holidays when agricultural work was light. Few believed that such giving was selfless. The gifts signalled recognition of past service, or the promise of further patronage, or hints that the giver would look to the recipient for aid in the future.

It was also a time when the more prosperous in society could be approached for “tips”; customers found they were approached by their butcher’s or grocer’s assistants, litigants were approached by court clerks, householders were annually braced by anyone from torch-holders and crossing-sweepers to refuse-removers. The practice bordered on extortion, and this fifteenth-century edict from London, aimed at civil servants, was typically disapproving:

Forasmuch as it is not becoming or agreeable to propriety that those who are in the service of reverend men, and from them, or through them, have the advantage of befitting food and raiment, as also of reward, or remuneration, in a competent degree, should, after a perverse custom, be begging aught of people, like paupers; and seeing that in times past, every year at the feast of our Lord’s Nativity, according to a certain custom, which has grown to be an abuse, the valets of the Mayor, the Sheriffs and the Chamber of the said city – persons who have food, raiment, and appropriate advantages, resulting from their office – under colour of asking for an oblation, have begged many sums of money of brewers, bakers, cooks, and other victuallers; and, in some instances, have, more than once, threatened wrongfully to do them an injury if they should refuse to give them something; and have frequently made promises to others that, in return for a present, they would pass over their unlawful doings in mute silence; to the great dishonour of their masters, and to the common loss of all the city: therefore, on Wednesday, the last day of April, In the 7th year of King Henry the Fifth, by William Sevenok, the Mayor, and the Aldermen of London, it was ordered and established that no valet, or other sergeant of the Mayor, Sheriffs, or City, should in future beg or require of any person, of any rank, degree, or condition whatsoever, any moneys, under colour of an oblation, or in any other way, on pain of losing his office.

Despite such condemnations, this practice (which became known in English-speaking countries as Boxing Day) continued for hundreds of years. Employees of London banks and officials of the British Foreign Office were still soliciting such Christmas gratuities until well into the nineteenth century.

Throughout Advent and the Twelve Days of Christmas, certain social groups, usually at the margins of the community, were temporarily privileged and could demand gifts – or go “questing.” This was the season for individuals or parties to solicit food or money door to door in return for good wishes or a song. In England, this custom took many names: “mumping,” a word derived from gypsy slang or from the mumbling of toothless beggars, or “going a-corning,” that is, seeking gifts of grain. Or on December 21, St. Thomas’s Day, old women might go “Thomasing” or “gooding” (it was considered good for one’s soul to give). And thus this song sung at the gate by indigent women:

Well a day! Well a day!

St. Thomas goes too soon away,

Then your gooding we do pray,

For the good time will not stay.

St. Thomas grey, St. Thomas grey,

The longest night and shortest day

Please to remember St. Thomas’s Day.

The “Wassail Wenches,” “Milly Maids,” or “Wassail Virgins” were Englishwomen who, in return for alms, would sing a ca

rol such as “The Seven Joys of Mary” and present the giver with a drink from a cup of Christmas cheer. On the Continent, similar quests were called Klöpfelgehn in Germany and l’aguilanneuf or la guignolée in France; different age groups or classes would go out on different nights, some on St. Martin’s Day, some (particularly young women) on St. Catherine’s Day, others on the Feast of Innocents, New Year’s Day, or Epiphany. It was not unusual on these nights to see costumed figures dressed as wise men, King Herod’s guards, devils, or madmen. Questers particularly sought out houses where a birth had taken place during the year but avoided those where someone had recently died.

Among those groups whose status changed during the Christmas season were children, who were given freer rein to make a nuisance of themselves and seek out treats from their neighbours. In the sixteenth century, the poet Barnabe Googe wrote disapprovingly in rhyme of the custom:

Three weekes before the day whereon was born the Lorde of Grace,

And on the Thursday Boyes and Girles do runne in every place,

And bounce and beate on every doore, with blowes and lustie snaps,

And crie, the advent of the Lorde not borne as yet perhaps,

And wishing to the neighbours all, that in the houses dwell,

A happie yeare, and every thing to spring and prosper well:

Here have they peares, and plumbs, and pence, ech man gives willinglee …

Sometimes, the young carried branches or mistletoe, reminiscent of the strenae twigs* of the Roman Kalends (which is why to this day the French call New Year’s gifts étrennes). It was considered good luck to give to questers, especially as their demands were often backed up by threats: “May God plague you with diarrhea until next Christmas!” “May God send you rats with neither cat nor dog to catch them nor stick to kill them!” On the Greek island of Chios, the householder who skimped on Christmas treats would be wished cloven feet, and on the Scottish island of South Uist, this chilling malediction was laid on the tight-fisted:

Santa Claus

Santa Claus